Are Chicken Wings White Meat? The Surprising Truth About Your Favorite Snack

You're at a barbecue, grabbing a plate. There's the chicken breast, pale and lean. There are the thighs and drumsticks, darker and richer. And then there are the wings—golden, crispy, irresistible. You bite into one. It's juicy, flavorful, maybe even a bit richer than you expected. A question pops into your head, maybe for the first time: Wait, are chicken wings white meat or dark meat?

Most people would guess dark meat. They feel richer, they're attached to a highly mobile joint, and let's be honest, they just seem more fun—which we associate with indulgence. But the official answer, according to both poultry science and the USDA, is clear: chicken wings are classified as white meat.

So why the confusion? And more importantly, why does it matter for how you buy, cook, and enjoy them? That's where things get interesting. This isn't just trivia; understanding the "why" behind this classification will make you a better cook. I've been grilling, smoking, and frying wings for over a decade, and I've seen how this one piece of knowledge changes everything from marinade time to cooking temperature.

What You'll Find in This Wing Guide

The Simple Science Behind "White" and "Dark" Meat

It all boils down to one protein: myoglobin. Myoglobin stores oxygen in muscle cells. Muscles that are used constantly—like the legs and thighs that support a chicken's weight all day—need a steady, on-demand oxygen supply. They're packed with myoglobin, which gives the meat a darker, redder hue.

Muscles that are used for short bursts of activity, like the wings (for brief flight or flapping) and the breast, need less constant oxygen. They have lower levels of myoglobin, resulting in lighter-colored meat.

From an anatomical standpoint, the edible meat on a chicken wing comes primarily from the pectoralis minor muscle. This is the same muscle group that gives us the breast, just a smaller, more tendon-laced part of it. The USDA's official standard classifies all meat from the front half of the chicken (wings and breast) as white meat, and the rear half (thighs and legs) as dark meat.

White Meat vs. Dark Meat: The Practical Differences

Knowing the science is one thing. Feeling it in your cooking is another. Here’s how white meat (like wings) and dark meat (like thighs) actually differ on your plate.

| Characteristic | White Meat (Wings, Breast) | Dark Meat (Thighs, Legs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Muscle Fiber | Fast-twitch (for short bursts) | Slow-twitch (for endurance) |

| Myoglobin & Iron Content | Lower | Higher |

| Intrinsic Fat Content | Lower (in the muscle itself) | Higher |

| Connective Tissue | Less (except in joints) | More |

| Cooks... | Faster, can dry out if overcooked | Slower, more forgiving, stays juicy |

| Flavor Profile | Milder, cleaner "chicken" taste | Richer, more savory, "gamey" notes |

Notice the potential contradiction? Wings are white meat, yet they often taste richer. That's the wing's secret. While the muscle fiber is white meat, the wing is a high-activity joint. It's laced with more connective tissue (collagen) than the breast and is wrapped in a generous layer of skin and subcutaneous fat. When you cook a wing, you're rendering that fat and breaking down that collagen, which creates a mouthfeel and flavor that mimics dark meat.

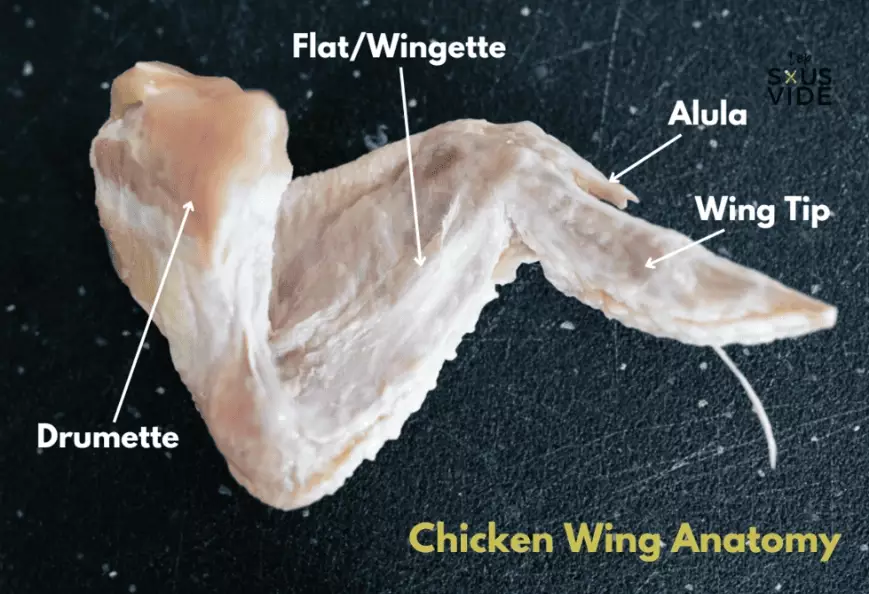

Wing Anatomy Breakdown: Drumette, Flat, and Tip

A whole chicken wing has three parts, and this is where people get tripped up.

The Drumette (The "Mini Drumstick")

This is the part that looks like a tiny drumstick. It's a single, meaty piece around one bone. Because of its shape, everyone assumes it's dark meat. It's not. It's 100% white meat from the pectoral group. The meat is a bit more concentrated and tender than the flat because of how it's attached to the bone.

The Flat (or Wingette)

This is the middle section with two parallel bones running through it. It has less outright meat than the drumette, but many connoisseurs (myself included) prefer it. The meat is sandwiched between the bones and that wonderful skin, and it has a higher concentration of connective tissue. When cooked perfectly, this connective tissue melts, and the meat pulls cleanly off both bones in one satisfying bite. This is the part that most strongly "feels" like dark meat due to its texture.

The Tip

Almost no meat here. It's skin, cartilage, and bone. Its purpose is to provide surface area for rendering fat and getting crispy, or to add flavor to stock. Most pre-cut wings you buy have this removed.

So, no matter which part you're eating, the edible muscle tissue is white meat. The experience is modified by its location and structure.

The Cooking Implications: How to Treat Your Wings Right

This is the pay-off. If you treat wings like dark meat (thinking they're forgivingly fatty), you might undercook them, leaving rubbery skin and chewy connective tissue. If you treat them like a lean chicken breast, you'll overcook and dry them out. You need a hybrid strategy.

1. For Crispy, Pub-Style Wings: Recognize the lean meat needs protection. The skin is your ally. Use high, dry heat (baking at 400°F/200°C or higher, air frying, or deep-frying). The goal is to quickly render the subcutaneous fat and vaporize moisture on the skin's surface to create crackling crispness. This process simultaneously cooks the interior meat just to done. A baking powder rub (a trick I learned from a restaurant chef) helps by altering the skin's pH for better browning and blistering.

2. For Fall-Off-The-Bone, Saucy Wings: Here, you need to tackle the connective tissue. This requires either slow, moist heat or a two-step process. You can braise wings in sauce for an hour or more. My preferred method for party wings? Pressure cook plain wings with a cup of water or broth for 10 minutes. The steam and pressure break down collagen incredibly fast. Then, toss them in sauce and finish under a broiler or on a hot grill for 3-4 minutes to caramelize the sauce and crisp the skin. It's a game-changer.

The common mistake I see is baking wings at 350°F (175°C) for 45 minutes. That's the worst of both worlds—too low to crisp the skin effectively, too dry and long for the lean meat, often yielding leathery results.

Your Wing Questions, Answered

So, the next time you pick up a wing, you'll know the secret. You're holding a piece of white meat that's been dressed for success—wrapped in a flavorful jacket of fat and connected with just enough collagen to make it interesting. Understanding this lets you move past guesswork. You can now choose a cooking method with purpose: high heat for crackling texture, or slow heat for succulent tenderness. That's the power of knowing what's really on your plate. It turns a simple snack into a lesson in anatomy, chemistry, and good taste.

So, the next time you pick up a wing, you'll know the secret. You're holding a piece of white meat that's been dressed for success—wrapped in a flavorful jacket of fat and connected with just enough collagen to make it interesting. Understanding this lets you move past guesswork. You can now choose a cooking method with purpose: high heat for crackling texture, or slow heat for succulent tenderness. That's the power of knowing what's really on your plate. It turns a simple snack into a lesson in anatomy, chemistry, and good taste.

February 7, 2026

February 7, 2026 4 Comments

4 Comments