White Meat on a Chicken: Your Ultimate Guide to Buying, Cooking & Enjoying

Let's be honest. When someone says "white meat on a chicken," a specific image pops into most people's heads: a dry, tasteless, hockey puck of a chicken breast. It's the dieter's sad staple, the meal prep martyr. But what if I told you that reputation is entirely undeserved? That the white meat—primarily the breast, but also the tender inner part of the wings—can be the most succulent, flavorful, and versatile protein in your kitchen? After years of cooking professionally and at home, I've learned it's not the cut that's boring; it's how we've been taught to treat it.

The white meat comes from the chicken's breast and wing muscles. These muscles are used for sustained activity (like standing), which means they are fueled by a different type of muscle fiber than the dark meat legs and thighs. They contain less myoglobin, hence the lighter color, and generally have less fat running through them. This is the source of both its health appeal and its cooking challenge. The U.S. Department of Agriculture notes it's a fantastic source of lean protein, but that leanness means it has less margin for error.

Quick Bites: What's in This Guide?

What Exactly Is the White Meat on a Chicken?

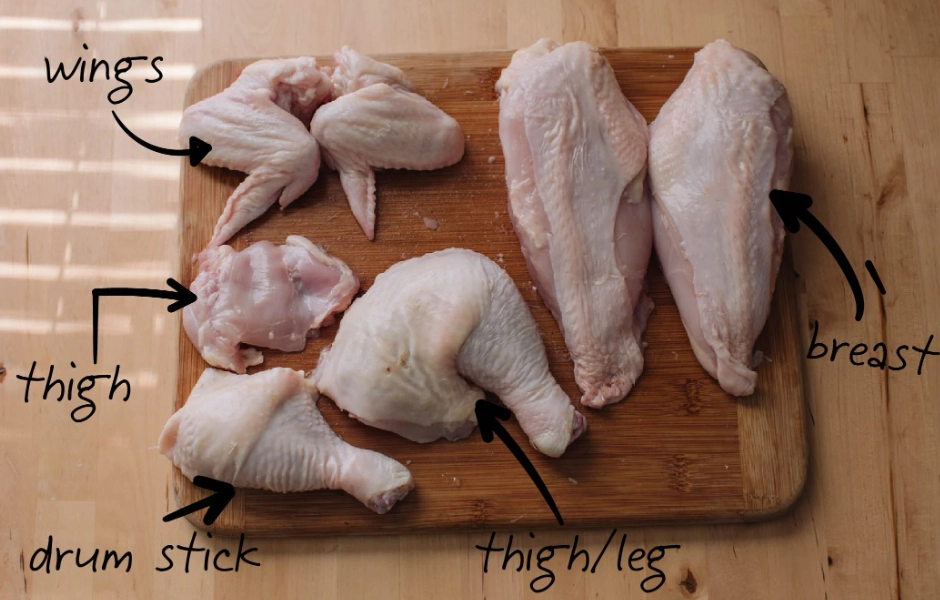

We throw the term around, but let's get specific. On a whole chicken or when buying parts, the white meat refers to:

- The Breast: The two large pectoral muscles. This is the main event. A single breast is often sold split into two halves (the "breast halves" you see at the store).

- The Wingettes (or Flats) and Drums: Mostly, yes. The meat on the smaller wing bones is white meat, though it's often overshadowed by the skin and any sauce.

Here’s the thing most recipes don't tell you: not all breasts are created equal. Size varies wildly. A massive, plump breast from a mature hen will behave differently than a smaller one from a younger bird. The bigger one will take longer to cook through, and if you don't adjust, you'll have a burnt outside and a raw center.

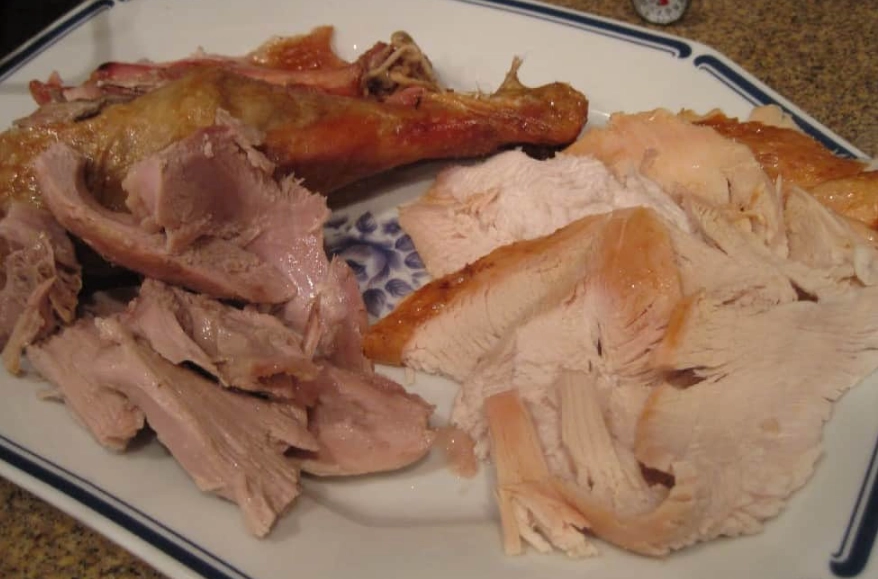

White Meat vs. Dark Meat: A Quick Breakdown

It's not just color. Dark meat (thighs, legs) has more fat and connective tissue, which makes it more forgiving and inherently juicy. White meat is leaner, cooking faster and firming up at a lower temperature. Treating them the same is the first mistake.

How to Buy the Best Chicken Breast (It's Not Just About Price)

Walking into the poultry section can be overwhelming. Here’s how I decide, cutting through the marketing labels.

Look at the Color and Texture: It should be a pale pinkish color, not gray or yellow. The surface should look moist but not slimy. Avoid packages with lots of liquid pooling at the bottom—it often means the meat has been frozen and thawed, losing moisture.

Decoding the Labels:

- Air-Chilled: This is my go-to. Chickens are cooled with air instead of being dunked in cold water. They absorb less water, so you're not paying for water weight, and they tend to sear better because the surface is drier. The flavor is also more concentrated.

- Organic/Free-Range: For ethical and potential flavor reasons, these can be better. The birds usually have more space, which can lead to slightly more textured meat. I find the flavor less bland. It's a noticeable difference in a simple grilled chicken dish.

- "Natural" or "No Hormones Added": Mostly meaningless in the US. By law, poultry cannot be given hormones. It's a marketing ploy.

Boneless vs. Bone-In: Boneless, skinless is convenient, but you're sacrificing two big flavor and moisture allies: the bone and the skin. Cooking a breast with the bone in acts as a heat buffer, slowing down the cooking and adding richness. The skin protects the meat and gets deliciously crispy. For a Tuesday stir-fry, go boneless. For a Sunday roast where you want maximum flavor, buy bone-in, skin-on and remove the skin yourself after cooking if you must.

How to Cook Perfect Chicken Breast: The Non-Negotiable Rules

This is where the magic (or tragedy) happens. Forget everything you think you know and start here.

1. The Preparation Step Everyone Skips

You must create even thickness. A chicken breast is fat on one end and thin on the other. If you cook it as-is, the thin end will be sawdust before the thick end is done. Here are your options:

- Pounding: Place the breast between plastic wrap or in a zip-top bag and gently pound with a rolling pin or pan until it's an even ½ to ¾ inch thick.

- Butterflying: Slice it horizontally almost all the way through, then open it like a book. This creates a larger, thinner cut perfect for stuffing or quick cooking.

This one step eliminates 80% of dryness problems.

2. Seasoning is Not Just Salt and Pepper

Salt needs time. Sprinkle kosher salt on your breasts at least 30 minutes before cooking, or up to overnight in the fridge (uncovered on a rack for the best texture). This "dry-brining" allows the salt to penetrate, seasoning the meat deeply and helping it retain its own juices. A wet brine (soaking in salted water) also works but can make the texture a bit spongy if overdone.

3. The Temperature Rule You Must Obey

Throw out the old "cook until no longer pink" advice. It's unreliable. You need a digital instant-read thermometer. It's the single best investment for cooking any meat. The USDA recommends cooking poultry to 165°F (74°C) for safety. Here's the pro tip: pull the chicken off the heat at 155-160°F (68-71°C). Carryover cooking will raise the temperature those last few degrees while the meat rests. Cooking it to 165°F in the pan guarantees overcooked, dry meat.

The Resting Period is Non-Negotiable. When you pull the chicken off the heat, the juices are rushing to the surface. If you cut it immediately, all that flavor and moisture pours out onto your cutting board. Let it rest, tented loosely with foil, for 5-10 minutes. The juices redistribute back throughout the meat. You'll see the difference.

Recipes & Techniques That Actually Work

Let's move from theory to practice. Here’s a comparison of the most reliable methods, based on outcome and effort.

| Method | Best For | Key to Success | My Rating for Juiciness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Searing & Oven Finishing | Weeknight dinners, golden crust | Get the pan very hot for the sear, then transfer to a 400°F (200°C) oven to finish gently. | 9/10 |

| Poaching | Meal prep, salads, shredding | Use a flavorful liquid (broth, herbs), keep it at a bare simmer (170-180°F), don't boil. | 8/10 (for tenderness) |

| Grilling | Summer BBQ, smoky flavor | Medium-high indirect heat. Sear over direct heat, then move to the cooler side to cook through. | 7/10 (needs careful temp control) |

| Sous Vide | Perfect, consistent results every time | Set your water bath to 145-150°F (63-66°C) for 1-4 hours. Finish with a quick sear. | 10/10 |

| Baking ("Roasting") | Hands-off cooking for multiple breasts | Use a rack on a sheet pan for air circulation. Brine first for best results. | 6/10 (can dry out easily) |

A Foolproof Pan-Seared Chicken Breast Recipe (Serves 2)

- Take 2 boneless, skinless chicken breasts. Pound to even ¾-inch thickness. Pat very dry with paper towels.

- Season generously with salt and pepper 30 minutes before cooking.

- Heat 1 tbsp oil in a heavy stainless steel or cast iron skillet over medium-high until it shimmers.

- Add breasts. Do not move them for 5-6 minutes, until a deep golden crust forms.

- Flip, cook for 1 minute, then add 2 tbsp butter, 2 smashed garlic cloves, and a few sprigs of thyme or rosemary to the pan.

- Tilt the pan and baste the chicken constantly with the foaming butter for 3-4 minutes.

- Check temp. When it hits 155°F, transfer to a plate, pour the garlic-herb butter over, and rest for 10 minutes.

This method creates a restaurant-quality crust and unbelievably juicy interior. The basting is the secret weapon.

Your Chicken Breast Questions, Answered

The white meat on a chicken doesn't have to be a punishment. It's a blank canvas, a lean protein powerhouse waiting for you to treat it right. Ditch the fear of dryness. Grab a thermometer, a rolling pin, and some salt. You're about to change your mind completely.

Join the Conversation